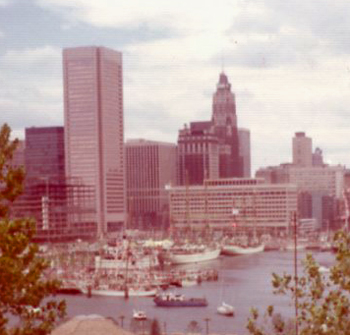

Baltimore in mid-July 1976 when the tall ships visited for the U.S. Bicentennial.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

Baltimore Saturdays

August 1, 2016

Twenty years after my father's death I have to remind myself that the saintly "Big Neal" oftentimes drove me crazy when I was a young man. Some of the irritation was due to my having yet to be, as Mark Twain was of his father, amazed at how smart mine had become by the time I reached manhood. In my case, I was well into majority when the dawn about Dad broke forth.

Otherwise we were two very different people. He was the popular ex-Georgetown basketball player who read a good book now and then, but who knew authors more by name than by their work, who kept The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball under the bed with The Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius. I was the non-athlete who disappointed everybody -- except my father -- in being non-athletic, who read books, then started typing them when I was 12, who collected collections, who tried such things as making lead copies of coins in plaster molds and who played and planned with our trains.

The trains were the first knitting of the bond between Dad and me. He had his childhood Lionel train from 1926, accumulated more sets and accessories before I was born. He was a pioneer collector by the time he came home from work one day to find, to his dismay, that I had pulled the trains out of storage and had strewn them all over the living room with their being no hope of ever repacking them just for Christmas. Baltimore, 35 miles away, was where the bond was fleshed and boned.

The Pikesville Armory

In 2016 the Maryland National Guard Armory in Pikesville (just across the Baltimore city line), built in 1903, closed forever. It was a dumpy venue for train, gun and pet shows with a men's room that flooded, but it will always be a hallowed hall to me. Dad and I went to train meets there for eleven years starting in 1968. I can think of no other place where after almost four decades I can remember so many moments and the exact spots where they happened: buying this piece, seeing that piece we couldn't afford (and never seeing it again), talking to a certain fellow collector.

Those long-ago meets were almost as much about socializing with the brethren as they were about trading. Most men, including my father, wore jackets and ties. We got to know several local gentleman in the true sense of the word: T. Milton Oler whose forebears molded ornamental plaster and who invited us to his antique-and-curio-filled Regester Ave. house a couple times; Hugo Keuhn, tall as my Dad, who summoned us to his Moyer Ave. domicile to pick up a valuable prize that he had claimed for us after we had departed before the drawing; Al Franceschetti ("Franchetti"), a Brooklyn transplant who had worked for Lionel and who made replacement parts. Others included Jerome Williams who started Williams Electric Trains in his Laurel, MD, garage, and his assistant, a short kid my age named Mike Wolf.

The armory's interior in 2008, little changed from the early 1970s.

A quality meet like Pikesville attracted dealers and collectors from all over, including a real-life ex-Nazi. Present at Pikesville one March was Gustavo (Gustav) Reder all the way from Madrid. Reder's fellow collectors probably never knew that "Don Gustavo," German-born and educated, had been a Nazi who worked in Joseph Goebbels' propaganda tentacle in Spain in the 1930s and '40s. Reder must have kept a low profile; U.S. intelligence concluded that he did not actually exist. Unscathed in Spain by Nazism's defeat, Reder held railroad-related jobs in Madrid and contributed articles to The Train Collectors Quarterly.

The Ladies Join Us

Like most women of their generations, my mother and grandmother frequently went on Saturdays to the big department stores in downtown Washington: Woodward & Lothrop ("Woodies"), Hecht's, Kann's and Lansburgh's. My Dad and I would kill our time going to Corr's Hobby Shop at 9th and H and occasionally a little hole-in-the-wall, Keane's Model Railroad Shop (proclaimed by a neon sign) on the very brief G Place. Keane's was for model railroaders who had been at it since 1939 and who were comfortable with buying boxes of wood and metal bits that they somehow fashioned into rail vehicles.

Every time I go to Baltimore, I remember those places and people of four decades past that are gone, especially when I'm homing and see the sky's glow fading to purple and black as evening comes on.

That routine ended with the Metro subway construction of Metro Center and Gallery Place Stations. All the streets around Woodies were covered with thick wooden beams. Finding a parking space became difficult. I remember a Saturday night in November of 1970, standing on the steps of St. Patrick's Church with Dad, waiting for Mom and Nana to emerge from Woodies with all its famous animated Christmas window displays agoing. Another church nearby was chiming Christmas carols such as Hark The Herald Angels sing. A light snow was falling. That was the last time we went Saturday shopping in downtown DC.

My parents decided that it might be easier to drive 35 miles up the BW Parkway than to find parking in the excavated shopping district of Washington. Thus eyes turned to Baltimore and its downtown department stores: Hutzler's, Hochschild-Kohn and Stewart's all lining Howard Street. My Dad and I looked in Model Railroader for a hobby store we could visit while the womenfolk shopped. We found one: M.B. Klein, Inc., est. 1913, on the corner of Saratoga and Gay Streets.

Stepping In Anticipation

Our first visit was very auspicious. We saw a really cool item and waited in suspense while young Ted Klein calculated the price in U.S. dollars from Swiss francs. $15.00! Corr would have wanted $30 or more for the same thing if he had it. That was the first of many tremendous bargains. In addition to the half-yearly sojourn to the Pikesille meet, we went to Klein's at least once a month over the next several years. Klein's became my parents' go-to place for my Christmas and birthday presents. How could my father afford it? He played all-night poker every Friday and he always won (Another story).

Klein's Gay Street store, painted red in its latter years.

A visit to Klein's began with stepping in anticipation from the glare raised by the Gay St. sidewalk and the white-painted storefront into Klein's interior, an entrance that required eye-adjustment. Inside the door on the left was a display case full of goodies. Klein's always had a tremendous selection of unusual items, imports, even old trains. Once we bought a whole layout and had to borrow a station wagon to bring it to Bethesda.

If Ted Klein didn't have it, he would order it. I learned that there were such things as models of Polish National Railway (Polskie Koleje Panstwowe) passenger cars. To the delight of my Krasnopol-born grandmother, who was taught to appreciate her nationality and heritage, I displayed a promise of similar discernment by yearning for a set.

Those were still the days of the Iron Curtain and the cars were made in East Germany. Thinking it was an impossible order, we approached Ted Klein. He flipped through a wholesaler's thick catalog. The PKP cars were available for pick-up in three weeks. They joined the collection during my grandmother's last year with us. While I've had to sell most of the treasures we got from Klein's, I still cherish those cars.

HO Ga. Polish National Railways car made behind The Iron Curtain

Hobby-store owners tend to be sociopaths. I should say tended because hobby shops, once common in post-World-War II suburbia and center cities, have pretty much gone the way of TV and radio repair shops. The only joy in the life of the miserable creatures who ran train and model outlets seemed to come from charging top dollar to the occasional customer whom they resented and wanted gone if he wasn't spending money.

St. Ignatius, built 1856, at Calvert and Madison Streets.

Model railroaders and train collectors loved their hobby enough to put up with these ogres and pay their prices (if they could), but the dealers were in trouble if a place run by a friendly and polite staff that sold at tremendous discounts was in town. Klein's was always crowded, with a long line stretching from the cash register far back into the store. In all of Baltimore in the 1970s, there was only one other hobby shop that sold new trains.