AUTOBIOGRAPHY

How Green Was My NIH

January 10, 2016

It's a warm, summer Sunday morning in Bethesda, Maryland. I feel the heat all the more in my jacket and tie. My parents and grandmother and 7-year-old I are walking from a parking lot the couple hundred feet -- Is it even that far? -- to the entrance of The National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, Building 10. We are on our way to Mass in the chapel on the 13th floor. The sun lightens the pink of Building 10's bricks, the green grass in the circle before the entrance and, on nearby knolls, the leaves of pine and deciduous trees that comprise the wood between Building 10 and West Cedar Lane.

There is not a soul in sight, no movement. We are a like a Star Trek crew that has just beamed down to a planet where all the inhabitants have vanished. The only sound is the insect sawing that rises to a crescendo and then dies off. Outside the main entrance there are lily ponds and goldfish. In the lobby, sunny because it is glass-walled on three sides, is an exhibit about the Pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem where Jesus cured a man on the Sabbath.

This is NIH in 1968. You can drive through an ungated entrance, park right outside the biggest building on campus in a lot that has spaces to spare. There is room for goldfish and a reminder of Christ in a U.S. Government installation.

Nearly 50 years on, I laugh at the idea of our driving to that easily-had, convenient parking space that is so inconceivable in the 21st century. We lived a distance of two suburban blocks from Building 10: one block down Locust Avenue, the second block down and up West Drive through the woods of NIH's serene campus. The Clinical Center, with the three large windows of its top-floor chapel, loomed over our backyard. We could have walked, but walking anywhere in those days just wasn't done. Everything seemed miles away.

With Nana's supervision, of course, I got the forceps or whatever was requested by the surgeon upstairs, placed it in the capsule, shoved the latter into the receptacle and watched it get sucked away.

Not only was the Clinical Center's chapel our preferred place of worship, my maternal grandmother, who lived with us, worked in its basement-level Central Sterile Supply from 1958 to 1971. Her shift was from 2 to 11 p.m.

Again, because two blocks was way too far to walk, especially at night, even though the path was lighted, my Dad would drive over at 11 p.m. to pick up Nana. I would often still be awake, listening to Felix Grant on WMAL, when she came home and checked in on me.

On Friday nights I would go with Dad to collect Nana and then we would drive up Rockville Pike to Burger Chef. This was located where the McDonald's is now at the corner of Marinelli Rd. and Rockville Pike across from the White Flint Metro Station. There was no Marinelli Rd., no Metro, just Burger Chef, a neon and light-bulb illuminated beacon of white, blue, and orange surrounded by trees, overgrown vacant lots and crickets.

When my parents were away on the occasional Friday, my grandmother would wait for me to walk home from school and then take me to work with her. These were the only times I walked to and from NIH as a child.

The Littlest Government Worker

Central Sterile Supply was located on a basement level of Building 10. In CSS' precincts, reusable supplies such as hemostats, scalpels and glass syringes were burned clean of contaminents in huge ovens called autoclaves. It was a fascinating place for this 7-9-year-old with its maze of aisles lined by shelves and storage cabinets and equipment such as hand drills for boring through skulls into brains. Most of the staff were African Americans and pasted up in a few places were photos of Rev. Walter Fauntroy, Washington, DC's first and long-time delegate to the U.S. Congress.

I helped out. Dirty supplies -- I have no idea what they were contaminated with -- were placed on racks with wheels that rode on rails and sat atop a cart. One pushed the cart up to and docked it with the autoclave which had corresponding rails. Then one rolled the rack into the autoclave, sealed the door shut and turned on the heat. This was heavy work and probably caused the heart attack that forced my grandmother to retire from NIH in 1971. She was 67 then, but having labored since she was an early teen, she would have stayed at her job indefinitely.

When the supplies were sterilized, they were restocked. I remember placing rubber caps on hundreds of glass syringes. I think plastic, disposable hypodermics were not in use yet. I also slapped sterilized stickers on things. I took leftover stickers home and slapped them on things at home. I'm sure that among my possessions there remains to this day something with a May 1969 sterilization sticker on it.

As I ascended Medical Center's long escalator, back then having no canopy and open to the sky, a huge, heavy tree branch blew across the opening. The escalator brought me up into sideways blowing rain that seemed six inches deep on the sidewalk.

NIH in those days still used an old-fashioned pneumatic tube system which I thought was extremely cool. A capsule bearing a paper order arrived in Central Sterile Supply. With Nana's supervision, of course, I got the forceps or whatever was requested by the surgeon upstairs, placed it in the capsule, shoved the latter into the receptacle and watched it get sucked away. Capsules traveled to a central location somewhere in the basement where employees read their addresses and inserted them into the appropriate destination tubes.

At dinner time we went to the cafeteria. I ate only hamburgers then. Relatives commented on it, thinking I was in some grave danger of malnutrition. We would get a hamburger sealed in plastic from a vending machine, take it back to the dimly lit, shadowy locker/break room. I miss dimly-lit, shadowy rooms of the '60s. They were relaxing. There we heated the hamburger in what was a primitive microwave oven. 1969 me thought these hamburgers in plastic were delicious. 2015 me thinks they're disgusting.

The last adventure of the evening would be the two-block walk home in the dark. Outside the main entrance at 11 p.m. idled a DC Transit GM Fishbowl bus ready to take the evening shift as far as Ivy City, a Northeast Washington neighborhood near D.C.'s railroad yards. In the age of the subway, no bus from NIH even crosses the District line. Down the sidewalk along West Drive we would walk and up Locust Ave. to our house.

In the late 1960s, The NIH chapel was my parents' preferred place of worship and we forewent our parish about half of Sundays to go to Mass there. I suspect it was because NIH Masses were shorter. NIH chaplains didn't dally when most of the attendants were falling over from chemotherapy and leaking brain-holes etc. The chaplains were Jesuits, a Fr. Armand Guicheteau from Georgetown University -- whom my grandmother liked -- and later, Fr. Eugene Linehan. More on Linehan below.

What ended our Sundays at NIH's chapel was the advent of Saturday night vigil Mass. NIH did not offer it because on Saturdays, the chapel was transformed by the rotation of a turnstile into a synagogue.

On NIH's vast parking lots, many of which are now covered by buildings and the currently fashionable landscaping of overgrown grass and weeds (butterfly sanctuary), I learned how to parallel park in preparation for my driver's license exam. My Dad told me, "The State of Maryland may give you a license, but you're not driving until I give you a license." We attached boards to broomsticks so that they would stand upright as markers and I spent many a spring of '77 hour maneuvering the old Chrysler New Yorker between them from the right or the left.

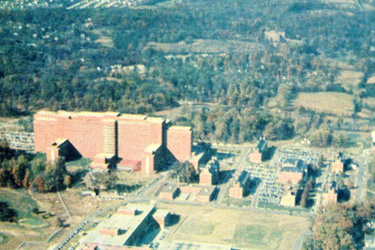

Building 10 dominates the NIH campus around 1960. The Capital Beltway was a few years in the future when this photo was taken.

By the late 1970s my parents, Mom as a member of the parish Ladies of Charity and Dad, a member of the St. Vincent de Paul Society, had begun visiting the sick at NIH. The patients who were in the Clinical Center because they had strange diseases to be studied, were mostly from out of town, even from other countries. Building 10 was the home of the original "bubble boy," a kid with a severe blood deficiency who had to live in a sterile environment on the Clinical Center's 13th floor.