AUTOBIOGRAPHY

The Kid Who Listened To Felix Grant

April 15, 2018

Bedtime began with prayers with my Dad: the "Our Father," the "Hail Mary" and the Lesser Doxology (aka the "Glory Be"). Then out went the lights and on went an early plastic art-deco radio, Amplitude Modulation only, with a clock-like dial that glowed. From it emitted the soothing voice of WMAL's Felix Grant, "on hand" with his "album sound 'til Midnight" and various renditions of his theme, Tenderly.

How in the Age of The Beatles, The Stones, a 7-10-year-old kid listened to a very grown-up disc jockey playing progressive and Brazilian jazz I can only speculate. Both parents occasionally read me bedtime stories, but my father burlesqued them, separating and combining sentences until we were both hysterical. My Mom usually preceded me in slumber, succumbing during Perry Mason. The literary sendoff to dreamland devolved upon my live-in grandmother. However, as recorded in How Green Was My NIH, she worked until 11 p.m. and could only perform that loving service on weekends.

Around 1990 I suffered from insomnia, but the blessing was I was able to hear a lot of the great Mayhugh during his last couple years on WMAL.

The youth culture of the 60s was also kept at bay. I had no older siblings to bring bad baby boomer tastes, habits and immaturity into our house. Recorded music at 5210 was played on a 1940s phonograph with a felt-covered turntable. This cherrywood-clad machine surmounted a sturdy cabinet of matching wood containing mostly 45s and 78s going back to The Ten Freshmen and Charlie Fry's Million Dollar Pier Orchestra. When I was given a serious stereo in 1978, I used its 78-speed setting to play more Ten Freshmen, moving on to Ted Wallace and His Campus Boys and Irving Aaronson And His Commanders.

A Lotta Mas Que Nada

My speculation is that I've always been one who needs periods of soothing sounds. The mellow, focused Felix Grant filled that bill. Grant never talked about himself. He spoke in a virtual monotone only about the albums he was playing and their performers, once in a while interjecting an obligatory remark about the weather. I never developed a taste for the kind of jazz that Grant played, but I remember him talking a lot about Mose Allison, the messed-up 19th-century French composer Erik Satie, whose work accidentally sounded jazzy, and Sergio Mendes' Brazil 66. Grant and other WMAL jocks spun Mas Que Nada quite a bit. The other track I remember is some quartet's (Dave Brubeck?) rendition of Wang Wang Blues.

World Building in Silver Spring proclaims WGAY's tenancy ca. 1975.

One night the neat old art deco radio showed signs of going up in flames and was discarded. My Dad, who was a buff of radio mechanics from his youth when he built crystal sets, bought me a $100 Sony shortwave from Rodman's, the D.C. drug/liquor store that seems to sell everything. I could have listened to stations from all over the world, but I kept the Sony tuned to AM 630.

I occasionally heard the legendary Joy Boys (Ed Walker and Willard Scott) on WRC if we were driving on weekday evenings to the hardware store or Montgomery Mall. Otherwise WMAL was my radio companion all through the day. Listening to the news -- national from the ABC network at the "top of the hour," local at the "bottom." -- became a habit in my childhood. As I played with my cars and trucks on the carpet, the ABC Information guys -- all, it seemed, named Bob -- broadcast about Alexander Dubcek in Prague, then about Chappaquiddick, then about Charles Manson, then about Watergate.

WMAL's morning hosts were another legendary and inimitable duo, Frank Harden and Jackson Weaver. At first I thought there really was an old lady -- one of Weaver's many voices -- at the mike. For almost three decades Harden & Weaver managed to broadcast a fun and informative program, free of put-downs, griping, raunch and politics, unless you include The Senator, another of Weaver's voices who introduced the daily march at 7:25 a.m. They also had a time-slot for a daily hymn.

In those days before all-news radio, WMAL was the go-to station for traffic, weather and, when DC was menaced by its nemesis, the dreaded snowflake, school closings. With more stay-at-home moms and staff and students living close to their schools, the systems preferred to stare down rather than shut down. It's laughable now; it was maddening then. Sometimes it would be 8 a.m. My Mom would be cursing at having to drive me through four inches of snow and Montgomery County, which Catholic schools followed, would not have announced yet. I think we were in the car once when the blessed reprieve came. We went back inside to relax and laugh at Frank and Jack announcing that the Rinky-Dinky Day School was closed, not because of the snow, but because of a bartenders' strike.

At 10:00 a.m. started a 4-hour shift by Tom Gauger who began his show with The National Anthem. Gauger often played Broadway tunes, especially from the early 70s revivals of old shows.

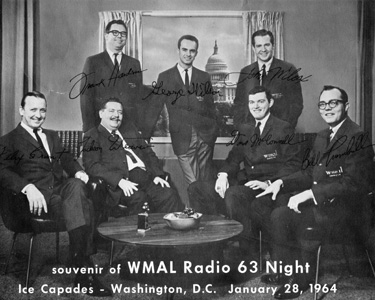

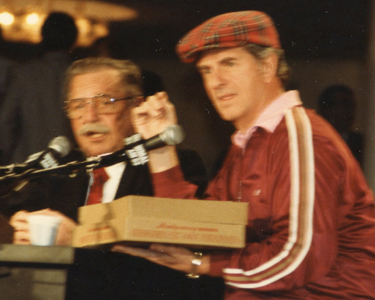

Sonny Jurgensen, Frank Harden, Jackson Weaver, Sam Huff at KenCen in 1985

WMAL was one of those stations that branded itself for grown-ups, i.e., no rock'n'roll. The music it played was what was then-called pop-standards or adult contemporary. The playlist included Simon & Garfunckel, Judy Collins, Helen Reddy, The Carpenters and a few who would be anachronistic in any other time but the early 1970s: "Hurricane" Smith, Bobby Vinton, Tony Orlando and Dawn. Tie a Yellow Ribbon 'Round the Ole Oak Tree was played incessantly in 1973-74. Another one was Kenny Rogers' huge late 70s hit, The Gambler. My Mom covered this frequently for the benefit of my poker-playing father.

Tom Gauger was followed by Bill Trumbull. Trumbull, who covered the late afternoon and early evening, was eventually paired with Chris Core, making up, at first, "Two For The Road" and then the "Trumbull & Core Show." If Trumbull and Core was supposed to be an evening rush-hour Harden & Weaver, they weren't. They were good radio company, but they ventured into airing pet peeves. Core is the only personality from those great days who is (in 2018) still employed in DC radio as a commentator.

Felix Grant's jazz program was, in its heyday, from 7 p.m. until Midnight. Occasionally I was awake long enough -- not a good thing for a 9-year-old who had to get up for school -- or up early enough to hear the all-night man, Bill Mayhugh. My Mom, early to rise as she was early to bed, listened to Bill a lot as she slumped at the kitchen table with her coffee and cigarettes. She said that Mayhugh always sounded like he was going to burst out crying.

Around 1990 I suffered from insomnia, but the blessing was I was able to hear a lot of the great Mayhugh during his last couple years on WMAL. Like Grant, he played albums, but it was Tony Bennett and the kind of music that should be played at 3 a.m. when, as F. Scott Fitzgerald said, it's always a dark night of the soul.

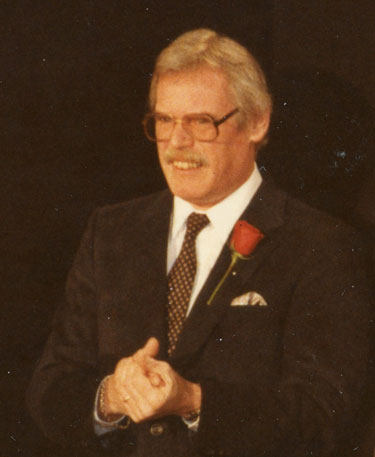

I met Bill one night when a date and I attended a concert in Georgetown that Bill was emceeing. He pulled into the parking space next to us. When I told him I used to listen to him when I couldn't sleep, he exclaimed, "You're the one!" I introduced him to the lady friend as a "radio legend" and he told her, "That means I'm old." He later sent me a tape of some of his on-air interviews with music legends.

WMAL's substitute and weekend personality was John Lyon. When John's two daughters, Kate and Sheila, disappeared near Wheaton PLaza on Good Friday 1975, WMAL and its owner, then The Evening Star, kept The Lyon Sisters in their news for over a year afterward, until The Star sold the station to ABC.

WMAL began its decline by pushing Felix Grant out with Ken Beatrice in 1977.

One of the leads the news team repeated was that a man in a brown suit with a tape recorder had been interviewing children, including the Lyon Sisters, at the plaza that day. As it turned out, the tape-recorder man story was fiction that originated with Lloyd Lee Welch, who pled guilty to abduction charges almost 43 years after the girls vanished.

For some reason I was always keyed up on Sunday nights, likely because I had no time to relax on the day of rest. My Mom insisted that we go out for a drive every Sabbath. We left late and came home late. I had to eat restaurant food that I did not like. I did not begin to enjoy these all-day excursions until flea markets were included on the itinerary. Also as I hated school, Sunday nights were like the night before facing a firing squad.