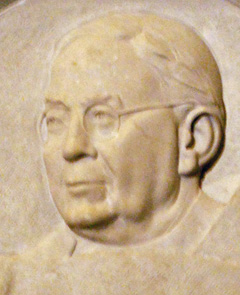

Cardinal O'Boyle And The 1963 March On Washington

(July 23, 2013)

Because he was taught by his small-town Pennsylvania family and faith community that human beings are created in God's image, my father, as an Army Air Corps private in World War II, thought nothing of crossing the segregated army's racial barriers to play basketball with African-American soldiers.

When he and my mother moved to Washington, D.C. in the 1950s, they met African American professionals for the first time. My mom worked in the office of The United States District Attorney for D.C. Headed by Oliver Gasch, this office that tried Jimmy Hoffa was a rookery for many future judges (and one U.S. Senator) including a young lawyer who later became a noted African American jurist. My mom could not believe that this educated man had been forced by the Separate-But-Equal Doctrine to sit behind a screen in his law school classes. Thus my parents became aware of a great wrong in American society.

Even before they arrived in D.C., their fellow Northeasterm Pennsylvanian, a man of identical background, Archbishop Patrick O'Boyle, was already quietly integrating the Catholic schools in the archdiocese. It was the first thing O'Boyle commenced when he took up his bishopric in 1948, several years before the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision overturned separate-but-equal in public schools. The bishop even got the anti-Catholic Washington Post not to draw too much attention to the effort. It took a lot of guts to desegregate schools in a southern city. Even some of O'Boyle's priests, among them the rector of St. Matthew's Cathedral, were vehemently against it.

O'Boyle spent much of his priestly vocation seeking the welfare of African Americans. That was not unprecedented among Irish clergy. The common experience of being treated as less-than-humans, as the Irish were treated by Anglo-Saxons, invoked the occasional special sympathy.

As a young seminarian at Mount St. Mary's in the 1820s, John Hughes, later the bishop who built St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York, earned his tuition in part by overseeing the seminary's slaves. Around the 50th year of American independence, a few years before William Lloyd Garrison came on the scene, Hughes wrote and published poetry looking to the day when liberty would be extended to all. From The Slave:

Hail Columbia, happy land,

Where those who show a fairer hand

Enjoy sweet liberty.

But from the moment of my birth,

I slave along Columbia's earth

Nor freedom smiles on me...

Beneath the burning heats of Noon,

I, poor slave, court the grave.

O, Columbia, grant the boon!

In addition to desegregating Catholic schools -- and some parishes where African Americans had to sit in the back pews -- O'Boyle developed other programs to aid blacks of all faiths in his archdiocese. One of these was Fides House, a facility in one of DC's poorest neighborhoods where volunteers lived and provided aid to the denizens.

The archbishop moved Fides House to larger quarters off North Capitol Street and assigned to its staff a LaSallian Christian Brother novice/Catholic University student named Joseph Charles Gennett aka "Brother Declan Charles, FSC."

Joe Gennett, a close friend of mine in his last years, left the Brothers of The Christian Schools for family life, but I believe that he was a saint with an uppercase "S." He told me of the wretched poverty, of chopping mountains of wood on cold winter days for the people to burn in their stoves and of the time he took a badly injured black girl to a whites-only hospital. Its medical staff refused to treat the little girl because of her skin color. That is until Joe fixed his business-meaning eyes on them and growled, "You're going to treat this girl!"

Decades after his Fides House experience, Joe would load up his old, green Buick Electra with Thanksgiving dinners and deliver them to lifelong friends who still lived in poverty in Swampoodle.

A great friend of Cardinal O'Boyle's, Joe Gennett, being one in mind on race with O'Boyle, gave me insight into His Eminence's approach to racial justice. O'Boyle was completely color-blind as everyone of any race was supposed to be. Past injustice was no excuse for victims of bigotry to become bigots themselves. The purpose of the Civil Rights movement was to provide an equal opportunity that was clearly lacking for African Americans in the first half of the 20th Century. That was how sympathetic people such as my parents, Joe Gennett and O'Boyle thought.

Then in the mid 1960s, progressivism was inundated by the power hungry and Marxist. My father used to call them "the tools of communism" which, I believe, was a very apt description. For a pedigree, read Jonah Goldberg's Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left.

Colorblindness was the last thing these people who think in terms of Marxist classes wanted. African Americans were a favored and aggrieved class. No white jury, for example, could do them any justice. With regard to race relations and inequalities, it would always be 1963. As with all things of the past, decades of advocacy for people of color like that of Patrick O'Boyle's were seen as worthless, especially if they were motivated by religious faith. Religion itself is an instrument of tyranny.

Cardinal O'Boyle's gentle, subtle, firm and truly pioneering efforts for racial justice have been dismissed to obscurity because he didn't fit the liberal profile of a hero. Instead he was a very conservative man, in most ways, who was motivated by the Catholic faith and morals, not by envy, ego, powerlust, the boredom of fulfilled, affluent, suburban life.

Likewise forgotten is O'Boyle's significant role in the August 28, 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

For that event at which Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his "I Have A Dream" speech, O'Boyle did much more than give the invocation. According to biographer Morris J. MacGregor, the cardinal's involvement assured that August 28, 1963 "would be remembered for Dr. King's stirring rhetoric rather than a diatribe against John Kennedy and Congress."(1)

O'Boyle supported many 1960s civil rights protests that became historical landmarks, as long as they were peaceful. He was enthusiastic about the March on Washington and agreed to say its opening prayer. A little-known fact about Catholic involvement in the march was that the Knights of Columbus donated $25,000.00 for the lodging of Catholic clergy who attended.

Less keen on the event were the ever-calculating Kennedys, President John F. and his Attorney General brother, Robert F. They feared that the march would be seen as a protest against them and the slow pace of civil rights legislation, being held up by their fellow Democrats, going through Congress.

The brothers' apprehension was probably justified. One of the speakers, 23-year-old Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee chairman, John Lewis, today a U.S. Representative, planned to give a not very non-violent speech in which he would promise a new Sherman's March. After one hundred years, that undertaking still resonated unpleasantly with white southerners.

Lewis fleshed out the plan by vowing to pursue a "scorched earth" policy to "burn Jim Crow to the ground." Deeply buried in the rhetoric was the qualification that all this conflagration would be allegorical and non-violent.

After seeing an advance copy of Lewis's speech, O'Boyle threatened to withdraw from the event. A standoff with Lewis then endured almost to the opening hour of the speeches. Lewis agreed to moderate his words. O'Boyle gave his invocation. Thus the day is remembered for Martin Luther King, Jr.'s I Have A Dream speech, one of American oratory's greatest.

(1) Morris J. MacGregor, Steadfast in The Faith: The Life of Patrick Cardinal O'Boyle, The Catholic University of America Press, 2006.

|

|---|

| Copyright 2013 by Neal J. Conway. All rights reserved. About this site and Neal J. Conway nealjconway.com: Faith and Culture Without The Baloney |