Odd Hanger-On: A Profile In Catholic Creativity

3/2/2013

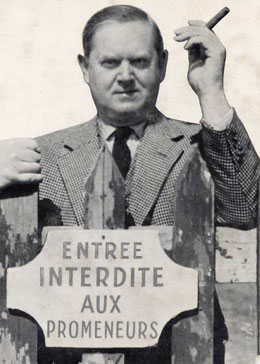

Had he more control over his fate, Evelyn (pronounced with a long capital E) Waugh would a) have made a career of being a hand-craftsman, perhaps drawing illuminated manuscripts and would b) have not included the feminine "Evelyn" among his given names. His two others that he found equally detestable were Arthur and St. John.

In autobiographical fiction, Waugh described himself as having been a little boy "acutely sensitive to ridicule."(1) Growing up in the London suburbs in the early 1900s, he loved the high Anglican services that his family attended. Serving as an altar boy, he "rejoiced in my nearness to sacred symbols"(2) At home he drew pictures of angels and saints.

However the course of Waugh's faith would be that of many young people in The Twentieth Century who attended church-affiliated secondary schools which turned out to be institutions that either deliberately or incompetently divested their students of religious habit. Even though his passion was imitating the calligraphy and illuminations of medieval monks, Waugh was, by the time he went to Hertford College at Oxford University, a professed atheist.

As he wrote in his best-known novel Brideshead Revisited, Oxford in 1921 was "a place where men walked and spoke as they had done in [Cardinal] Newman's day." Although Waugh had no known contact with them, among the faculty in the university's many colleges then were fellow-future-authors C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.

Oxford University was also in Waugh's youth an institution in which about half the students left without earning degrees. Waugh was among those. He ran with a crowd of what we would now call "hipsters," what were then called "bright young people." Many of them were rich, privileged and able to convince others of their superiority and genius as well as they convinced themselves. They were the "bored sophisticates," precocious, posing egos who comprised a bazaar of the avant-garde that was being mass-produced and wholesaled after World War One.

"Then I climbed the sharp hill that led to all the years ahead."(3)

An aimless university drop-out in debt -- Living beyond his means was one of his lifelong penchants -- Waugh worked as a teacher at a boarding school. He considered becoming a carpenter. He was so depressed in true "bored sophisticate" style that he attempted suicide by swimming out to sea. There he encountered a swarm of jellyfish that with their stings drove him back to land and life.

The least and last of his aspirations was to be an author. He turned to writing for money. Having several literary friends and a father who was a director of a publishing firm, Chapman & Hall, were a big help in pursuing that line.

His first novel, Decline and Fall, was published in 1928. Based on his experiences as a schoolmaster. it was a comic romp somewhat in the style of Waugh's favorite author and the best-seller of the day, P.G. Wodehouse. Waugh's writing can be described as more serious Wodehouse with sex scenes and social commentary. Decline and Fall's theme was stock among early Twentieth-Century atheist intellectuals such as Nietszche: the uninhibited, amoral exercise of will, throwing oneself on a whirling wheel of life and enjoying it, perhaps mastering it, being the hammer rather than the nail.

Yet strewn on the path well-worn by godless feet were glittering nuggets of Chesterton. The young intellectual was developing a suspicion of intellectuals. In the ridiculous figure of "Professor" Silenus, the architect who declares that "All ill comes from Man," the reader sees Schopenhauer and Sartre. Mr. Prendergast is a type of clergyman who became all too common in the Twentieth-Century, one who does not believe in God. Professor Lucas-Dockery is the first of many Waugh characters who is guided to disaster by theories of uncommon nonsense rather than by common sense and actual experience.

As Waugh's star rose, he tired of his bright young friends, spoofing them in his second novel, Vile Bodies, and married the niece of the Earl of Carnarvon, Lord of Highclere Castle, financier of the discovery of King Tut's Tomb. Mrs. Waugh's first name was, believe it or not, Evelyn. In short order She-Evelyn cheated on He-Evelyn and he in equally short order divorced her.

Underneath the hard carapace that Waugh had grown, he was probably deeply wounded in his insecurity-beset ego. Another type of character, the shallow woman who has extramarital affairs, recurred in his novels.

It would be best to call Waugh's conversion to Catholicism in 1930 a first step in a faith journey that progressed slowly the rest of his days, becoming apparent in his novels more quickly than in his personal life and behavior. At heart, the 27-year-old believed in common sense and that the universe had design and purpose. His attraction to Catholicism was strictly intellectual and aesthetic. He saw the priest as a "craftsman" who "stumped up to the altar with [his] tools and set to work."(4) The Catholic church was a well-made thing and it was logically true.

As was the case with his contemporary Francois Mauriac, Waugh's newfound faith began to influence his work. The original version (5) of A Handful of Dust (1934) is a study of the vanities written of in The Book of Ecclesiastes. Tony Last fights to keep his grand house which in the end passes to fools. A man who "never really thought about [God] much," Tony is led to a South American jungle by one of those quack ideologue professors of Waugh fiction and ends up in a kind of Hell ruled by a devil who forces him to read the works of a writer who, unlike Tony, took God more seriously.

Throughout the 1930s, Waugh roamed the world and spent much of his time writing travel pieces. He was sent as a correspondent to cover the Italo-Ethiopian War but was fired for filing reports written in Latin. In 1937, after getting an annulment, he married his second wife, Laura, a Catholic cousin of She-Evelyn, and with her had five children.

Waugh was not cut out to be a family man; he had no understanding of or rapport with his offspring. They irritated him. He spent much of his time away from home, writing in hotels and country houses, aboard ships. When present at the Georgian mansion that he couldn't afford, he limited his time with the kids to "ten awe-inspiring minutes" a day.

The Masterpiece

Came the Second World War, Waugh saw the conflict literally as a crusade to save Christendom from evil and barbarism as embodied in German Nazism allied with Russian Communism. He served in a force of British commandos who specialized in precursing invasions. How did a doughy, unathletic 36-year-old gain entry to such a tough fighting unit? The commandos couldn't refuse a man recommended by Winston Churchill.

However they could get him out of the way. Captain Waugh did not play well with other officers. In the 1950s he fairly accurately fictionalized his war experience in a trilogy of novels, Men At Arms, Officers And Gentlemen, The End of The Battle. Like the protagonist of these, nobly born Catholic Guy Crouchback, Waugh spent much of his war service behind desks, training, waiting for missions that were cancelled, dining out, trying to make himself comfortable, looking in at the club, interacting with unreliable allies and seeing very little action. Most of the latter was experienced during the British run from Crete before the Germans.

Like Guy, Waugh injured his knee in a practice parachute jump. He spent his time in recuperation writing his most famous and most Catholic novel. Its working title was The Household of The Faith. Published, it was Brideshead Revisited. Its pages are filled with beautiful prose including metaphors such as this:

My theme is memory, that winged host that soared about me one grey morning at war-time.

These memories, which are my life -- for we possess nothing certainly except the past -- were always with me. Like the pigeons of St. Mark's, they were everywhere, under my feet, singly, in pairs, in little honey-voiced congregations, nodding, strutting, winking, rolling the tender feathers of their necks, perching sometimes, if I stood still, on my shoulder or pecking a broken biscuit from between my lips until, suddenly, the noon gun boomed and in a moment, with a flutter and sweep of wings, the pavement was bare and the whole sky above dark with a tumult of fowl.

Brideshead Revisited is a study of the members of a noble Catholic family, the Flytes, who live in a grand house inspired by Castle Howard, a real edifice that resembles St. Peter's, and how they react in various ways to their Catholicism. Half the family remain faithful to the church. The other half rebel against the faith. However, they, at various stages of life -- spoiler alert -- all return to it. Sebastian the homosexual, alcoholic son and implied lover of narrator Charles Ryder becomes, as Sebastian's nun-like sister Cordelia characterizes him, one of the faith's "odd hangers-on," not the type one would expect to be a believing Catholic. That could be said of Evelyn Waugh himself.

Readers have often found the conclusion of Brideshead Revisited, specifically the sudden conversions of Lord Marchmain and Charles Ryder, who goes from being an atheist on one page to praying on the next, to be an unrealistic plot twist, difficult to swallow. However, it must be remembered that Waugh's embrace of Catholicism was itself a sharp, unexpected turn. Around the time he was writing Brideshead, he witnessed the actual deathbed repentance of a friend who had seemed recalcitrant.

Disillusioned Crusader

Peace found Waugh embittered. The war that had begun as his country's crusade against evil ended in his country's alliance with Soviet communists who had been half of that evil. England and its allies abandoned those who had fought with them, including Catholics, behind the Iron Curtain where they were slaughtered and oppressed by regimes that were as bad as Hitler's had been.

The Fanfare For The Common Man, too, surely made the author cover his ears and grimace. Waugh believed in a class system and that the nobility, imperfect as it was, was best suited to lead and uphold civilization as well as furnish its well-made and beautiful things. He looked with horror at the vulgar flotsam and jetsam rising on the postwar tides. His novels, including the war trilogy, cast more characters such as Hooper in Brideshead, men who had neither noble motivations nor classical educations, to whom History was about "humane legislation" and "recent industrial progress," small-minded men who were in over their heads when placed in leadership positions. "Fido" Hound in Officers and Gentlemen is incapable of using discretion and acting unless he receives orders. Ivor Claire, one of Waugh's less honorable upperclassmen, rationalizes his desertion to Guy Crouchback:

"And in the next war, when we are completely democratic, I expect it will be quite honorable for officers to leave their men behind. It'll be laid down in King's Regulations as their duty -- to keep the cadre going to train new men to take the place of prisoners."

"Perhaps men wouldn't take kindly to being trained by deserters."

"Don't you think in a really modern army they'd respect them more for being fly?"

One of the forms Waugh's disgust with modern Europe took was in his third Catholic novel. Plotwise it was historical fiction, set in the declining years of The Roman Empire.Its main character was Helena, the saint who uncovered the true cross. However in Helena's pages are many analogies between the empire of the mid A.D. 300s with civilization of the late 1940s: "huge, new shabby apartment houses;" sculptors who are incapable of creating art of earlier quality. Helena's husband Constantius makes a deal with a civil-war enemy wherein the latter will get away safely if he leaves his army where it can be massacred. She spends most of her life in what would become Twentieth-Century Yugoslavia where betrayals by the victors and communist atrocities that haunted Waugh had occurred.

Probably the only fictionalized story of a saint ever written in which there is coded sexual humor, Helena is also about the state of Christianity in the Twentieth Century. The title character, the red-haired, common-sensed, horsey-set daughter of England's King Coel, becomes a Christian because the faith seems so much more authentic to her than the other myriad myths and cults of the empire. The church's founder was a real person who died in a real place in a specific year. It has "accounts written by witnesses...knowledge handed down from father to son...the cave where he was born...the tomb where his body was laid."

However Helena comes upon her faith during one of its eras when the divinity of Christ is doubted by many Christians, when there are calls to tune Christianity to modernity, when the concrete things of the faith are overshadowed by abstractions such as "wisdom" and "peace."

Helena makes it her mission to find the true cross. "Just at this moment when everyone is forgetting it and chattering about the hypostatic union," she declares, "there's a solid chunk of wood waiting for them to have their silly heads knocked against."

Years of Confession

For much of his adult life Waugh suffered from insomnia often caused by the sleep-depriving fever that writers experience when their creativity is gushing, when they are "unable to put the pen down" and pulling all-nighters. On top of being an alcoholic, he became addicted to sleeping drafts that he concocted himself.

By the mid 1950s, he was experiencing audial and visual hallucinations and paranoia. After a family intervention, he turned even this low-point of life into a comic novel, The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold. In this work Waugh assesses himself as a welcomed and over-rewarded youth who had gradually assumed a "character of burlesque," casting himself as an eccentric, offering the world "a front of pomposity mitigated by indiscretion." He acted so, he said, to hide the fact that he was "modest" [humble, religious, moral].

He was probably one of those types who is pleasant when he is one-on-one with people, but who wears masks of aggression and antic when he is in public or a group. Thomas Merton, with whom Waugh developed a friendship, knew him as "a humble, self-lacerating soul, tortured by a sense of sinfulness." (6) In A Little Learning (1964), the first part of an autobiography that Waugh did not live to complete, he shared with readers his horror at the writings of his school days. "I was conceited, heartless and cautiously malevolent...I absurdly thought cynicism and malice the marks of maturity."

Evelyn Waugh died on Easter Sunday, 1966. He was a creative genius who undertook a journey that many of his century and its immediate successor are taking, a journey from the belief of childhood, through the abyss of youthful atheism and to a slow, climb up a sharp hill to renewed and firm faith.

(1) The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold, 1957

(2, 3) A Little Learning, 1964

(4) Diary entry as quoted on p. 464 of Stannard, Martin, Evelyn Waugh The Later Years 1939 - 1966, W.W. Norton, New York, 1992

(5) Some editions have an alternate, happy ending.

(6) p. 223 of Stannard, Martin, Evelyn Waugh The Later Years 1939 - 1966.

|

|---|

Evelyn Waugh In America "Every human being," Evelyn Waugh scolded a bewildered American hostess, "is born in sin. Original sin. But every American is born in extra sin -- the sin of treason to the British Crown...." (7) The devout Englishman visited The United States three times 1947-50. These were the zenith years of a remarkable era of about two decades in which Catholics were a powerful presence in culture and the arts. It was during this time that movies such as Going My Way and It's A Wonderful Life were made. Veteran Catholic authors such as Francois Mauriac and Waugh were at their peak; new writers such as Flannery O'Connor and J.F. Powers emerged. A mega-best-seller of the time was a book written by a Cistercian monk, The Seven Story Mountain. Evelyn Waugh edited the British edition of Thomas Merton's confession. Waugh visited the United States for various career purposes, including talks in Hollywood about filming his best-seller Brideshead Revisited. Although he was paid handsomely for the screen rights, an American movie never materialized. Brideshead and other books were not filmed until after Waugh's death in part because American censors would not pass a film in which a protagonist's adultery so prominently figured. To Waugh's dismay and certainly no surprise, the MGM people did not comprehend the religious aspect of the story, only the romance. In addition to a load of film-rights money, Waugh came away with delicious material for a viciously funny book about a commercial, godless society's approach to death, The Loved One. He traveled the whole country, exploring Catholic sites in Southern Maryland and Minnesota, making his hosts uncomfortable and earning fees from lectures. The most remarkable incident of his American visits was his lunch in New York with Dorothy Day, founder of The Catholic Worker movement. Given how the author detested the lower classes -- He seemed even to resent their having decent housing -- his meeting with Day is possibly one of the strangest in Catholic history. Yet afterward he donated some of his appearance proceeds to The Catholic Worker. Befriended by Time/Life magazine head Henry Luce and his wife, Claire Booth Luce, a Catholic, Waugh also took a $5000 commission to write an article on The Catholic Church in America for Life. Coming from a man who had affected boredom and disdain as he toured the country with his nose high in the air, who had been reported in the press to be an America-hater, Waugh's "The American Epoch in The Catholic Church," published in the Sept. 19, 1949 issue of Life, came as a complete surprise. Waugh begins with a review of how one racial, cultural or national branch of the church "bears peculiar responsibilities to the whole," at times when "Christianity seems dying at it center." He speculates that "Providence is schooling and strengthening [America] for the historic destiny long borne by Europe." He praises American Catholics, particularly the Irish, for fostering loyalty to a nation that isn't harbored at the expense of loyalty to an ancient faith and for building an educational system that transforms "a proletariat into a bourgeoisie" and provides a "grounding of formal logic and Christian ethics" to "young men who are going out to be dentists or salesmen." Lastly, Waugh assured those of other nations who see America as inextricably part of their future that there is a Christian/American way of life, not the dreaded one that they see in American movies. |

Waugh and Homosexuality If Catholics have heard of Evelyn Waugh at all, they are likely to think of him as the guy who wrote about homosexuals. This is mainly because of two cinematizations of Brideshead Revisited and their depictions of the relationship between Sebastian Flyte and narrator Charles Ryder. The Brideshead cast also includes Antony Blanche. Sebastian and Antony are based or real people whom Waugh knew at Oxford. Homosexual characters appear in other Waugh works, Grimes the pedophile in Decline And Fall, Apthorpe with his boot fetish in Men at Arms and Corporal-Major Ludovic in Officers and Gentlemen. These characters are either ridiculous or sinister. Even Sebastian Flyte is a jerk who slams the door of Brideshead Castle in Charles' face, later abandons him and imitates his father, Lord Marchmain in perfecting Lady Marchmain's martyrdom. Young men worshipping other young men is a common theme in English literature. Come to mind are Charles Dickens' David Copperfield (David and Steerforth); Thomas Hughes Tom Brown's School Days (Tom and Scud): A.J. Cronin's The Green Years (Robert Shannon and Gavin). Was Evelyn Waugh a homosexual himself? The answer is that he most likely was homosexual as a young man, but that he, like Charles Ryder, converted to heterosexuality after leaving the exclusively male worlds of Lancing School and Oxford. Young men of his class in his time as they grew to manhood had no contact with females other than their sisters. When adolescence opened their eyes to love, there were none but other boys around. This is something that Catholics who advocate strict separation of sexes in adolescence should consider.

|

| Copyright 2012 by Neal J. Conway. All rights reserved. About this site and Neal J. Conway nealjconway.com: Faith and Culture Without The Baloney |