Strong, Tall Tower: A Profile in Catholic Creativity

(July 30, 2012)

"The Brooklyn Bridge and I grew up together!" declared Alfred Emmanuel Smith. His birthplace and boyhood home on South St. was nearly under the Manhattan-side approach of the New York landmark. Ten-year-old Al and his father may have been the first non-construction people to cross the span before it was finished and opened in 1883.

The Smith Family belonged to the working, mostly Irish poor of the island's Lower East Side. It was a neighborhood around which a decades-deep reputation of crime and gangsterism had encrusted. A few blocks inland from the Smiths' riverside flat was The Five Points, an intersection notorious for its vice and violence. However Alfred Sr. and Catherine Smith would have none of that environment in their home. They taught Al and his siblings right and wrong and their lives were centered around St. James Catholic Church and supporting the neighborhood firefighting company. Such property and life savers were, in those days, social and community organizations as well.

Al Smith was a beneficiary of the parochial school system that had been set up in New York to bolster the Catholic faith of immigrants while educating them and enabling them to become good American citizens. He attended St. James school and was active in the parish into his young adulthood.

St. James put on amateur theatricals to raise money. Acting was Smith's hobby, but he tired of playing villains. For one thing, some of the neighborhood dimwits didn't understand that the shows were just pretend. However the reluctant "bad guy" kept taking the less choice roles because the productions benefitted an orphanage.

In school Smith demonstrated above-average intelligence and won medals in what we now call speech and debate, a highly valued part of the curriculum in those days. However, at age 13 when his father died, he had to leave formal education behind to become the family's principle breadwinner. For several years he worked at various blue collar jobs including one at the Fulton Fish Market. That stint gave him a lifetime repertoire of seafood allusions and analogies such as "handshake like a dead mackerel."

He came to public office as a creature of New York's Democratic machine, Tammany Hall. It sent him to the state legislature in 1903.

After several years of working in Albany and acquiring a knowledge of state government possessed by no other, Smith attracted public notice when he served on a factory safety commision that was appointed after 146 garment workers perished in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist loft fire.

In the political spectrum of a century ago Smith was a liberal advocating safe working conditions, the minimum wage, decent housing. He was one of the legislators who succeeded in changing a New York law that mandated that children be put in institutions if their fathers died, even if their mothers were fit. Smith called the Hill-McCue bill an "act to conserve the family life of the state."

As he rose to become the Empire State's governor, Al Smith would, in a biographer's words, "outgrow Tammany." He came out against the universally practiced patronage of the time and appointed experts, not cronies, to agency positions.

Having tried in 1924, he succeeded in winning the Democratic party's nomination for candidate for U.S president in 1928, running against incumbent Herbert Hoover. Repealing prohibition was a party plank. Smith spoke plainly against the Anti-saloon League, the Ku Klux Klan and lynching.

He was defeated in a landslide and did not even carry his home state. The country was happy with the economic boom occurring under a Republican administration.

In the face of the first Roman Catholic presidential nominee, the anti-Catholic elements that are ever-present in American society bared their teeth as viciously as they had in the decades before The Civil War. Myths about the church and the motives of Catholics that originated in 1600s propaganda returned to political discourse. Irving Stone enumerated them in They Also Ran:

"...[Smith] was building a tunnel that would connect with the Vatican; the pope would set up his office in The White House...no one could hold office who was not a Catholic; Protestant children would be forced into Catholic schools; priests would flood the states and be in supreme command..."

H.L. Mencken commented, "Those who fear the Pope outnumber those who are tired of the anti-saloon league."

While Al Smith's campaign for The White House failed, it created new interest in the political process and voting among women, particularly Catholic women, and among recent-immigrant ethnic groups.

In the end, Smith got the better part of it. The victor, Herbert Hoover, was blamed when the boom times were over. The loser, the man born under one New York City landmark, went on to build a New York City landmark of his own.

Empire State, Inc.

Like Alfred E. Smith, John Jakob Raskob was a cradle Catholic who had served as an altar boy. Like Smith, he had to drop out of school and get a job when his father died. He became personal secretary to Pierre S. DuPont.

When trusted with DuPont's money, Raskob augmented the chemical baron's fortune and made one for himself by investing in an up and coming company: General Motors.

He also deposited DuPont cash as well as his own into banks operated by Catholics, thus increasing their banks' assets and enabling them to lend to their communities. As the richest Catholic in the U.S. since Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Raskob was a celebrity among the faithful struggling to move up in America. Al Smith set it down as a coup when he got so prominent a big businessman to chair the Democratic National Committee.

However, among other super-rich, Raskob was considered to be a class traitor for working with the Democrats and Al Smith's campaign. General Motors forced him to resign his position as a director. When the 1928 election was over, Raskob, again like Smith, found himself out of a job.

Unemployed though he was, Raskob still had millions and the support of DuPont. He decided that he was going build a New York skyscraper just as another General Motors alumnus, Walter P. Chrysler, was doing. For that purpose Raskob started Empire State Inc. and put in charge the man who knew how to manage a New York City project better than any other: Alfred E. Smith.

By the late 1920s, it had become impractical to build skyscrapers like those that Woolworth, Singer and Metropolitan Life had erected earlier in the century, mere steeples that were intended to attract publicity or to brand companies. The Raskob/Smith tower was an investment. As many floors as possible had to turn a profit. That is why The Empire State Building has a squarish design up to the 86th floor, to maximize rentable office space. Its original design did not include the 16-story alumninum turret that has always distinguished it.

Except for a vaunted and then abandoned intention to use the building as a mooring mast for dirigible airships, the Empire State project was brilliantly planned and executed. Acquired from the Waldorf-Astors, who rebuilt their hotel farther down the street, the site at 34th St. and Fifth Ave. was a few blocks from most of the subway lines running through Manhattan. Al Smith ordered that wood from the demolition of the old Waldorf-Astoria be made available free to the poor for their cooking and heating stoves.

Actual construction began on March 17, 1930, St. Patrick's Day. Architects Shreve & Lamb designed the skyscraper's elements to be mass produced and assembled quickly. The steel framework was riveted together at the astonishing pace of one story a day.

In a little over a year, the Empire State Building was finished. On May 1, 1931, it opened. President Hoover threw the switch turning on its lights. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had succeeded Smith as New York's governor, joined the dignitaries on the 86th-floor observation deck. The E.I. DuPont Company was a major tenant. Walter P. Chrysler declined the invitation to attend.

It was Roosevelt who put to rest Al Smith's presidential ambitions for 1932 and beyond. For the rest of his life Smith worked for Empire State, Inc. often walking the 22 blocks between his home and office, chatting with the cleaning people if he was working late at night.

Of Alfred E. Smith and John J. Raskob, John Tauranac wrote, "The developers of the Empire State Building were hardly sleazy speculators whose goal was to build a schlock building with the intent of unloading it on some gullible buyer at the first opportunity. They wanted a first class building they would hold on to, a building that they would care for as stewards. They had entered the construction and real estate business for the long haul. They had made no little plans."(2)

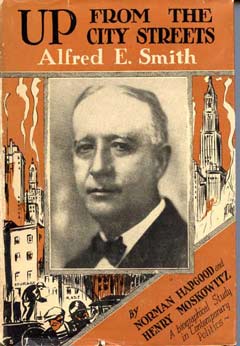

(1)Up From The City Streets: Alfred E. Smith, A Biographical Study in Contemporary Politics, Norman Hapgood and Henry Moskowitz, Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1927

(2)The Empire State Building: The Making of a Landmark, John Tauranac, St. Martin's Griffin, New York, 1995

|

|---|

Al Smith's favorite books were said to be The Book of Job and The Gospel of St. Luke. He declared that he believed in "the common brotherhood of man under the common fatherhood of God." In his day he was a liberal, but as biographers wrote of him in 1927, "He is a conservative in some respects, and always will be, and he never has been, and never will be, a radical in the sense of being interested in abstract, sudden and complete experiments based on guesswork."(1) Smith preferred to work for cooperation and did not care for the radical left, or anybody, demonizing classes of people. He believed that Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal was divisive. Later in life Smith supported Republican presidential candidates. "The operation of government is a science," he said, "It requires men who not only understand problems, but who understand men. Nearly every great problem in government is solved after compromise. If a man is to be successful...He must be able to disscuss a matter at hand intelligently with other men who disagree with him. It is impossible for him to get anywhere if he mistakes honest disagreement for antagonism...He cannot holler 'You came up from wall Street!' |

|

A hero among Catholics who hoped to move upward socioeconomically, John J. Raskob believed and preached that average people could attain wealth by investing regularly in the stock market over the long term. This has been proven true except at times when investors start treating the market as a horse race for quick gains. In the late 1920s, Raskob could see the bubble expanding due to such short-term speculation. He decided to put his own money into real estate. |

|

An artist's conception of the Empire State Building rendered when it was seriously believed that the tower could be used as an airship terminal. Only one dirigible ever docked at the top and that was just for a few seconds. It was realized that the wind currents over Manhattan's canyons created conditions that were too dangerous for maneuvering blimps. Soon after plans to use the turret as a mooring mast were abandoned, one of the building's early tenants, the National Broadcasting Company,, figured that the aluminum apex could be used as an antenna for a new medium that NBC was experimenting with: television. The Empire State Building has had many Catholic tenants over the decades. On July 28, 1945, employees were holding a Saturday morning meeting of The National Catholic Welfare Council on the 79th/80th Floors. On his way to join them was director Msgr. Patrick A. O'Boyle. On a whim, the monsignor stopped at his tailor's to pick up a suit, thus delaying his progress to the meeting. It turned out to be a fateful digression for the future cardinal archbishop of Washington, DC. A B-25 bomber, lost in the fog of that morning, slammed right into the 79th and 80th floors, killing 14 of the welfare council workers. While the loss of life was awful, the strong tower designed by architects Shreve & Lamb easily withstood the impact. It was open for business the following Monday morning. |

| Copyright 2012 by Neal J. Conway. All rights reserved. About this site and Neal J. Conway nealjconway.com: Faith and Culture Without The Baloney |