CULTURE

Antonio Cua and Ethical Argumentation

January 1, 2018

In 1984 a course on Aristotelian/Thomistic Metaphysics was not to be found in the catalog of The Catholic University of America.

Students got a smattering of The Philosopher and The Angelic Doctor in the required Philosophy 101. There was a good course on the Existence of God, good in that it was not called "The Problem of God," as if God were a problem. Unlike many Philosophy courses on God, it did not lead 20-year-olds to conclude that God does not exist. Rather it explored the methods of proving that there is a God (Ps 14:1).

There was also a nice Epistemology (study of Knowledge) class taught by a professor whose name I've forgotten but who wore brown pants to every meeting. The venerable Msgr. Robert Paul Mohan taught Ethics and probably saved many a Business major's soul (Trier-of-fact out on Susan Sarandon until Judgment). However for those like me who wanted to delve deeply into Aristotelian and Thomistic Metaphysics, there was nothing. The only "Metaphysics" was taught by Paul Weiss, a spry little Jewish man born in 1901 New York. Logic and Fallacy were touched upon in Ethical Argumentation taught by Confucian Antonio Cua.

How did it come to pass that America's official Catholic university (which CUA, not Notre Dame, is), an institution instigated by the pope of the Thomistic Revival, Leo XIII, served as side dishes the church's long-favored philosophers while promoting Twelve-Tribesmen and heathen to top chefs?

Some boilerplate history

Beginning in the 1960s, parties with their own agendas of change used the occasion of The Second Vatican Council to sell many Catholics on the idea that what had been used in the church for centuries had to be abandoned for or otherwise diluted with new stuff.

Along with a fear -- unfounded, as it turned out -- that they would be ineligible for federal student money, the esprit of makeover inspired Catholic colleges and universities to divest themselves of their Catholic identity. They literally locked it in storerooms or discarded it altogether. They were further ambitious to be like "the [poison] Ivies."

Whiff of ivy

Catholic U. never vandalized its identity as extensively as Georgetown or Notre Dame did, but it followed the trend a bit. Paul Weiss was just the sort of faculty member to fill the halls of Caldwell and McMahon with a whiff of ivy. Weiss had taught at Yale back in the days of William F. Buckley's enrollment. The old man, who continued his career at CUA into his 90s and lived to be 101, had the advantage of "looking like" a philosopher, just as the Dalai Lama or Francis the Talking Pope look like holy men. Of the two, DL is more adept. Weiss's Metaphysics was typical modern stuff, thinking about thinking and trying to figure out how and where the subject ends and the object begins.

To further prove that modern Catholic universities aren't intellectually incestuous, CUA hired Confucian Antonio Cua. However Cua was a real philosopher. Of a Chinese Philippino family, he spent his career exploring the points at which Eastern and Western philosophies intersect.

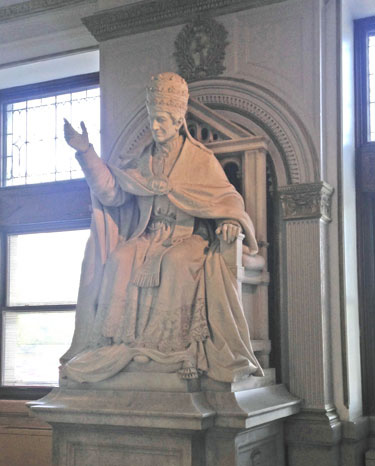

I took Dr. Cua's class in the then-unrestored, gloomy McMahon Hall, built 1890, with its attic still housing an aboriginal messenger-pigeon coop, its few graces covered over with firewall and its main foyer haunted by a life-sized statue of Pope Leo XIII. President Theodore Roosevelt rode uptown on horseback to admire the statue just after it was installed around 1905.

Having a name that matched the university's initials (CUA), Dr. Cua and the university experienced no end of mix-ups with the mail. A linguistic quirk of the doctor was pronouncing the short "o" ("ah") like the short "u" ("uh"). This had a comic effect when the professor talked about Immanuel Kant, as when he asked the class, "How many of you have had Kant?"

Dr. Cua's book was Ethical Argumentation: a Study in Hsun Tzu's Moral Epistemology.(1) Hsun Tzu was how Dr. Cua spelled the name of the 3rd-century B.C. Confucian philosopher, but his name seems to be more commonly known as Xunzi or Xun Kuang.

Aristotle, Hsun Tzu's more ancient (by 100 years) predecessor in the west, was concerned primarily with formal logic, such things as syllogisms and the opposition of propositions as described in the books of the Athenian's Organon. The problem with formal logic is that arguments can be formally logical, but materially untrue if the propositions are untrue. All animals have five legs. Unicorns are animals. Therefore unicorns have five legs.

Formal logic is also deadly dull. It can kill one's interest in Philosophy if professors spend too much time on it. It's possible that excessive focus on formal logic, rather than critical logic, assessing the truth of things, is the reason that some Theology students were turned off by Thomism in the mid-20th-century. I'm glad the diagramming was back-burnered for a bit of Confucianism.

Hsun Tsu emphasized the ethics of argumentation. He believed that argumentation is a method of addressing a matter of common concern, of working out a solution to a problem. Argument is not a contest or an exhibition of skills. As Unknown agreed, "Argument sheds light, not heat." Hsun Tsu's ideal leads one to recall the citizens of Greek city states (at their best) debating a problem or a 1950s Civics textbook describing how the will of the people smoothly becomes law and how everyone should be thankful that they live in a society where all viewpoints are heard in open and respectful debate.

According to Hsun Tzu, how one engages in argument reveals one's character. Contentiousness indicates a lack of concern for the problem. Isn't that true? The University of Lublin (Poland) philsophers, including Fr. Karol Wojtyla (Now Pope St. John Paul II) were interested in the behavioral implications of beliefs. Ideas have behavioral consequences. Hsun Tzu looked at the problem a posteriori: behavior has ideological causes.

The bottom line of ethical argumentation is: If someone is not in the true spirit of argument, if someone is misusing argumentation for selfish purposes or a desire for power, you don't have to argue with him.