Beloved Dinosaur: William Donald Schaefer, 1921 - 2011 Just about 38 years ago, if you drove into downtown Baltimore via Russell Street, you would -- somewhere around the Cat's Paw heel factory or the RCA Victor building crowned by a giant Nipper hearing his master's voice coming from the gramophone -- pass a city-government project sign whereon its boldest text read "William Donald Schaefer, Mayor." When he was newly elected, Don Schaefer was advised to erect such credit-taking signs by his fellow city-CEO, Richard Daley, Pere of Chicago. Like Daley, Schaefer was the product of a machine. He was born in the political rookery of West Baltimore from which many prominent Maryland officeholders, down to current Senator Benjamin Cardin, have come. With idealistic Jews who were truly interested in providing good government in its works, the apparatus functioned benevolently while operator-in-chief Irv Kovens was doing whatever he did behind closed doors. Schaefer, a Lutheran/Episcopalian/Mason who would have joined the restricted Maryland Club without a blink, knew to get up and leave when the doors were being closed. He warned his maker Kovens that he would support only whatever he, in conscience, thought was best. That vow was one he kept throughout his political life. It got him into trouble as Maryland's governor and as comptroller. Many Maryland Democrats may spit on his grave for being a Democrat governor who endorsed George H.W. Bush's reelection bid and for being buddy-buddy with the Little Newt Gingrich of Maryland, Gov. Bob Ehrlich. From his commerce in snipes with Gov. Parris Glendenning, we may postulate that Schaefer did not care for affluent-suburban liberals whose priorities are, for example, "the environment" and who are just shocked when a chief executive refers to female staffmembers and reporters as "little gals." If Schaefer was for cleaning up The Chesapeake Bay, it was because he was for the people who lived in its watershed, for their livelihoods, for their enjoyment of the bay's beauty. He ran for governor to keep the Sachs and Glendenning types from dominating Maryland. Nevertheless they do and Schaefer got hammered -- His style didn't help -- when he ventured from Baltimore's city hall to higher office. Once he was photographed outside M.B. Klein Model Trains at the corner of Saratoga and Gay Streets shaking hands and trading roars with Godzilla while Ronald McDonald looked on. The mayor/governor was a dinosaur himself, socially conservative but only too glad to net taxpayers' money that Washington was hurling into the air like confetti for urban projects back then. No one in those few decades ago, including most conservatives, cared about deficits or debt ceilings. In 1971, the year Schaefer was elected mayor, my parents and I started traveling to Baltimore regularly. Its old downtown shopping district along Eutaw and Howard Streets was thriving and less scary than DC's which was also torn up for Metro construction. While Mom shopped in Hutzler's, Hochschild-Kohn's and Stewart's, Dad and I went to Klein's train shop and other places around town such as The Enoch Pratt Free Library and the cathedral. In late afternoons we would drive out Edmondson Ave. past the side street on which Schaefer lived. He preferred remaining at his near-lifelong home, a modest rowhouse, to living in the governor's mansion in Annapolis. One could tell during Schaefer's reign that things were happening in Baltimore. Some of the projects that had been planted when Rep. Nancy Pelosi's brother, Tommy D'Alessandro was mayor were showing their fruit. The skyscraping United States Fidelity & Guarantee Building, completed around 1972, was a sign that private enterprise believed that Baltimore had a future. Schaefer's pet project, the Inner Harbor, was cleaned up nicely for the Bicentennial visit of eleven "tall ships" from around the world in 1976. I also remember going to a huge festival in the Polish neighborhood around Broadway and Eastern Ave. where Obrycki's Crabhouse still thrives among the bodegas. Every bus-stop bench in town was stencilled with the clumsy maxim "Baltimore's Best, Baltimore is Best." We occasionally saw Schaefer's dark green Cadillac Fleetwood in the VIP parking lot at Memorial Stadium during Orioles games.You noticed such things if you parked bumper-to-bumper in the ballpark's regular lots. Others spotted the mayor's car in Baltimore's century-plus-old "Block" of burlesque establishments. The official excuse for this was that there were no parking spaces at nearby city hall. I recall seeing Schaefer in person only once and that was, sadly, not in the performance of one of his grander stunts. He was merely playing Santa Claus at the new convention center, one of the concrete baubles in his crown. The notable thing about this appearance and it was somewhat strange: he did not say a word out loud that could be taken taken down in evidence, not even a ho-ho-ho. He just sat on a throne, whispering to children as they posed on his lap for snapshots and then he was gone. An antique toy-train display had brought us to the convention center that day. Schaefer retained his boyhood trains and in 2010, on the very same spot where he had played Santa, I suggested to an official of The Train Collectors Association that the still-living buff be made an honorary member. A politician who really cares about good government is a rarity and being one who cared was the basis of Schaefer's greatness. On the top of that was his understanding that alongside the federal money for projects, he needed the business community to play a part as well as the citizens of Little Italy and Pimlico and Overlea. There were no political "good guys" or "bad guys" -- at least publicly -- on the streets of Schaefer's Baltimore or in the surrounding suburbs. To connect with ordinary folks and get them believing was why Schaefer, a preppy wonk, moved in the circles of Godzilla and Ronald McDonald and otherwise goofed around. The TV spot that he made showing him having fun playing "trashball" is a masterpiece. It was the mayor's little part in the extraordinary and largely successful effort that was made 35-40 years ago to convince people to throw trash into receptacles and not on the ground. A positively hokey emanation of his let's-try-anything approach was the "Think Pink" project, but it got the folks in the streets to put up quarters and dollars for fixing the potholes in them. Where the old Cat's Paw heel factory stood now looms the M&T Bank Stadium for The Baltimore Ravens (which should be called The Phonenixes after what Schaefer went through with The Colts). A little north is Camden Yards and Babe Ruth's childhood home turned into a museum. This is all good, but Harborplace contributes mightily to America's obesity problem and is due for a reconception. While the greasy food joints were abuilding around the inner harbor, the old downtown a few blocks up imploded. Schaefer would willingly take the blame for this, but I don't think that he deserves it. There were currents flowing more forcefully than anything he could have countered them with. For example, the era of the big-city department store is over. Schaefer was never satisfied with his efforts. He died in April of 2011 probably believing that he had never done enough. He may in fact have done just enough. His urban renewal, dated though it now may be, kept Baltimore alive for a time when city makeovers are not about bulldozing the past but about refurbishing it. Baltimore has blocks and blocks and blocks of incredible and beautiful old buildings and charming spots, all gems waiting to be polished. |

|

|---|

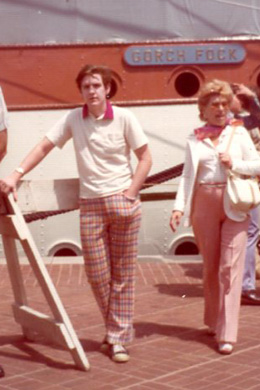

You can tell from the pants that it's the '70s. Fifteen year-old me in front of the tall ship Gorch Fock from Germany. The visit of these multi-masted, rigged ships in 1976 was a major milestone in Mayor Schaefer's effort to renew the environs of Baltimore's Inner Harbor. During the Bicentennial, the harbor surrounds were mostly vacant lots covered with neatly-mowed grass. Schaefer wanted lots of visitors, but he didn't want people getting used to the empty space which he intended to fill with Harborplace. |

|

2010: Forty-nine-year-old me on one of Harborplace's concrete plateaus with the Hyatt in the background. Getting Hyatt to build a hotel in a dicey downtown was a victory for Schaefer. Other Harborplace development was undertaken by James Rouse, builder of Columbia, Maryland and a man who had ironically made his fortune on the life being drained out of city centers for the nourishment of suburbs and malls. Thirty years on, Harborplace/Convention Center now hits one in the eye with a very dated 1970s vision. Bare concrete preponderates. On a hot day, the sun beats down brutally on the unshaded above-the-street walkways and expanses. Future makeovers should include fewer greasy-food chains, more trees and fountains and more tourists who are interested in the Poe, Mencken and Carroll Houses. |

For More About Big-Government Conservatives, Be Sure to Read: |

|

|

Patrick Cardinal O'Boyle: If Only He Had Known |

|

"One Flood Against Another:" A Review of Dapper Dan Flood |