TRAINS

Lou Hertz: Toy Train Genius

July 10, 2021

I can still see the letter from "L.H. Hertz" addressed to me in the mail pile when I got home from school. I wondered why a legend in toy train collecting would write to a 16-year-old kid. Although Hertz was not a member of the Train Collectors Association, he had seen my want ad in a TCA newsletter. I answered him; he wrote back. The letters are long lost.

One night many years later I got a phone call in response to another ad about Ives trains. The caller never identified himself, but I'm sure it was Hertz. We talked about Ives for 15 minutes. There was some feedback on the line, probably caused by an amplifying device on Hertz' end. He was hard-of-hearing.

Reading Louis Heilbronner Hertz' work, I, as many others, I'm sure, assumed that Hertz, who started writing prolifically about toy trains in 1935, was born around 1900. His output of the 1930s and '40s was so grown-up, so literary. When Hertz died in 1994, I was shocked to learn that he was actually born in 1922. He was 13 to 23 years old when he wrote erudite articles, built up a magazine and published three books, all the while befriending the Forcheimer Brothers of Dorfan Trains, William Ogden Coleman of American Flyer and Joshua Lionel Cowen.

The Ives Family, when 18-year-old Hertz showed up at their Connecticut farm around 1940 asking about the defunct Ives toy-train company, were flattered and gracious, but probably cast wondering glances at each other.

Hertz must have been sensitive about his youth for he lied about his age, claiming in 1936 that he was 19(1). When serious publisher Charles Penn wanted to hire Hertz to edit a new magazine, Penn had to apply to 16-year-old Hertz' father for permission.(2)

Lou Hertz was a New Yorker. Two addresses associated with him are an apartment on Riverside Drive near Hamilton Grange and a Victorian house with Tudor touches on the Scarsdale/Hartsdale border.

Lee Ridgeman, founder of Model Railroader's Digest, hoped that subscribers would pay $5.00 to have their train layouts pictured on its cover.

He appears to have been a prodigy, perhaps made so by disability. In his 1977 autobiographical interview, he reveals that his legs were paralyzed for about a year when he was a kid. (3) As a pre-schooler, he learned to read from an Ives train catalog. Elementary school found him delivering treatises to the other kiddies.

Birth of a hobby

Millennials of the 2020s who fill their work cubicles with Legos and other childhood toys probably would have been, in the 1930s, set down as looney and then sent home with severance. But back then, despite the sharp demarcation between childhood and adulthood, many men who had, as boys, played with the electric trains of the early 1900s, were forever under the spell of miniature railroading. As adults they could call it "Model Railroading," a new art made respectable by lifelike exhibits at the Chicago and New York World's Fairs and by two new serious magazines, Charles Penn's [Railroad] Model Craftsman, and A.C. Kalmbach's Model Railroader.

While he is mostly associated with Charles Penn publications, thirteen-year-old Hertz' first article about "tinplate," as toy trains were called, was published in Model Railroader in 1935. Forty years later, around the U.S. Bicentennial, Hertz again wrote a couple articles for Model Railroader and for early issues of Kalmbach's Classic Toy Trains launched a few years before his death.

This essay is about Hertz' early efforts in developing the hobby and his roles in shoestring toy-train publications. Said shoestrings broke very quickly.

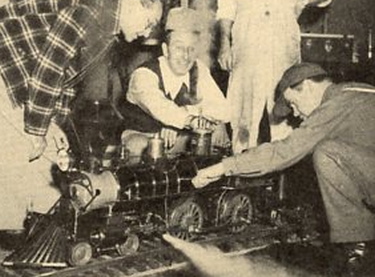

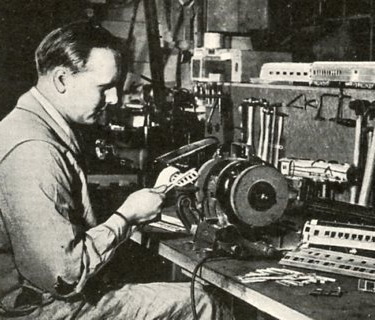

The realistic scale models of the 1930s, such as those furnished by Edwin P. Alexander, were very expensive. Most model railroaders worked with trains originally made as toys, perhaps altering the playthings to look more like models. An Ohio electrician named Delbert Henninger, whose career included wiring silent movie theaters for "talkies," was a master at making toy locomotives look (somewhat) more like the real ones.

Men interested in toy and model trains began finding and corresponding with each other. One was a Californian, Lee Ridgeman, who operated the Centinela Valley Railroad, an impressive (for the time), large layout of altered toys, collectors items and homemade structures.

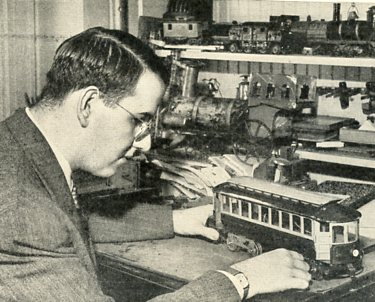

Professional modelmaker, author, founder of the Train Collectors Association, Edwin P. Alexander in his workshop around 1940. Alexander built models for the 1939 New York World's Fair and later for the Smithsonian/B&O Railroad Museum.

In 1936 Ridgeman typed a couple of his letters in a newsletter format (4). He was encouraged to turn it into a magazine. Model Railroader's Digest was born.

Ridgeman reproduced the third issue by having his wife typewrite about 15 copies of each(5). That one production may have sufficed for Mrs. Ridgeman for Vol. 1, No. 4, the 4-page May 1, 1936 issue was professionally printed at a cost of $20.00.

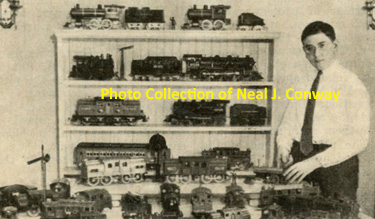

In that issue Lou Hertz' byline was on "The Antique Collector and Historian," "the first column ever devoted to obsolete tinplate equipment." The June issue of MRD led with Hertz' description of his Hartsdale Central Railroad, a "Christmas" layout that sprawled all over the Hertz' Riverside Dr. apartment. The same number also included the first of many pieces by the talkie-movie electrician Delbert Henninger on what became his "Seneca Union Lines." The September MRD listed Mrs. S.R. Heilbronner, Hertz' grandmother, as a booster.

The MRD of October included an announcement, with rates for advertising, by Hertz of a Standard Catalog of American Tinplate Motive Power, first edition, $2.00. This is a project that Hertz had been working on from childhood, using illustrations from toy train catalogs. However he quickly realized that such a compilation would be far from comprehensive. While the standard catalog never materialized in book form, it was an early concept of the number lists and price guides that train collector clubs and publishers issued decades later.

Like all early toy train magazines and books, the Model Railroader's Digest was very gray with text and short on illustrations. Much of its column space was given over to subscribers describing their layouts. In those times (and indeed, until the advent of desktop publishing) it was expensive to process photos for printing.

As sources of information about toy trains, early publications are not very useful. They are filled with inaccuracies, speculation and instructions that make even less sense than modern how-to's with illustrations. It took decades of a growing number of collectors exchanging information and building an "economy of collecting" for truly informative material about toy trains to emerge.

"You know, sometimes I think I ought to write an article entitled "Terrible Mistakes I've made...," Hertz said in 1977 (6), Some of the errors I made forty years ago are still picked up and repeated by people who think that because something is printed, it must be so!"

Lee Ridgeman claimed that he was not interested in making money on Model Railroader's Digest nor was he a magazine promoter. While he got want ads at 25 cents each and even display ads from American Flyer and The Model Railroad Shop, Ridgeman was out of the picture by 1937. Vol. II, No. 1 of that year is headlined with "Lee Ridgeman Relinquishes The Reins of M.R.D."

Professionally laid out and printed on quality gloss paper, MRD was now in the hands of Dudley M. Olney and 15-year-old Hertz, himself. It contained more display ads including one placed by "Richard Maerklin," the American representative of the famous German company, advertising the venerable firm's new and sensational HO trains.

But only two issues of MRD were published in 1937. Hertz reappeared in 1938 as managing editor (still in his minority) of Charles Penn's new Miniature Railroading. Over the next 13 years, Hertz wrote a column, "Along The Tinplate Track" for Penn's [Railroad] Model Craftsman.

Meanwhile in May, 1939, Model Railroader's Digest was revived with Hertz as sole publisher and editor.

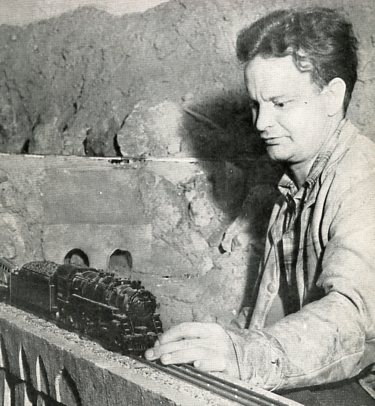

Whatever its profitability, MRD's content flourished under Hertz until it was discontinued in 1941. There were illustrations on almost every page and more display ads to pay for them. Sections of Hertz' Standard Catalog of American Tinplate Motive Power were inserted for cutting out and three-hole-punching in a binder. Readers were introduced to collectors and operators who became famous in the hobby such as John A. Markham of Windsor, Ont. and Edwin P. Alexander who ran ads touting his model store at 13 E. 40th St. near Times Square.

Many of the want ads in MRD were placed by Hertz himself. He occasionally published his own articles under the pseudonyms of "Walter Nafford" of "R.D. Colvin."

Riding The Tinplate Rails

In 1944, during World War II and its paper shortage, Charles Penn published Hertz' first major book, Riding The Tinplate Rails. In later decades this and other out-of-print Hertz books about tinplate commanded high prices. It's likely that profiteers/thieves checked Hertz books out of public libraries, pretended to lose them, made retribution by paying the cover prices and then made a profit by selling the books for $50, $75, $100.

The Hertz-book bubble was burst by modern publications containing more accurate information and most importantly, lots of photographs, moreover in full color. Like all early tinplate publications, Riding The Tinplate Rails has an illustration/text ratio heavy on the latter.

Some of the content is also downright silly, particularly in the chapter "Publicity and Satire." Hertz reports that the Errol Flynn/Olivia De Havilland 1938 movie Four's A Crowd disappointed tinplaters because it did not treat model railroading in a serious manner. In 1944, the nitpicking train nerd had become established among the hobby's personality types.

In another chapter Hertz writes of a "Model Railroad Museum [to be] established." Like his catalog of tinplate motive power, such a concept, the TCA's Toy Train Museum in Strasburg, PA, materialized decades later, but Hertz, not being a member of the TCA, was not involved in its establishment.

Riding The Tinplate Rails' final chapter is "On The Trail of The Ives Company" in which Hertz' recounts his trips to Connecticut to interview Ives Family members and others connected to the famous American toymaker. He got Harry Ives' daughter, Virginia to take him through the old Ives factory on Holland Ave. in Bridgeport. Hertz' research resulted in Messrs. Ives of Bridgeport published in 1950.

Probably his best book, Messrs. Ives of Bridgeport is a good human-interest story about the people involved in a toymaking operation and their adherence to values of a higher plane than profit.

Magazine bubble

In the early 1950s, with the post-World-War-II boom in full swing, with people having more money for hobbies and space in new suburban tract housing to indulge them, electric trains reached their peak of popularity. The two major American manufacturers, Lionel and American Flyer, jumped through hoops, sometimes very degrading for company personnel, to get their trains featured on the most popular TV programs such as I Love Lucy and The Jackie Gleason Show.

1950-51 saw at least three new toy train magazines spring up like rye. None lasted beyond 1954.

Issued out of Philadelphia, Electric Trains was the most short-lived. Its publisher, Fox Schulman Enterprises, brought in Hertz as publisher and editor of the last two of its only six issues. Two other collectors who became well-known in the future, Don La Spaluto and Harry P. Albrecht, already staffed Electric Trains as Editorial Advisors.

Hertz in 1941 posing with a Lionel trolley from the 1910s. Even before World War II, this 8-wheel car was a prized and highly sought-after rarity.

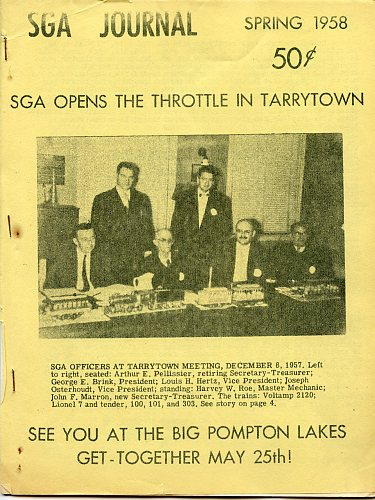

An issue featuring Walt Disney's outdoor railroad included a photo of Disney animator Ward Kimball who shared his genius in toy tran publications many times over in years to come. Mentioned editorially were long-time Tampa, FL, hobby dealer, Chester Holley and train club leader John Marron.

But Electric Trains lacked focus. It tried to be all things to all types of readers: kids, adult hobbyists, train collectors, HO operators, the hobby trade, each a very different readership. The magazine touted a "Don Blake's Railroaders' Club" represented by the drawing of an engineer, first depicted as a strapping young man, then as an older avuncular guy in overalls.

Whoever the hell "Don Blake" was (another Hertz pseudonym?), he kept apologizing for not being able to keep up the with the correspondence of his engineer's club. The magazine's final number came out in April 1952 entitled Hobby Railroading, The Magazine of Electric Trains. It included a spread on the Bridgeport Model Train Show, organized in part by Hertz, whereat Virginia Ives Cook presented prizes to little kids who had likely never heard of Ives Trains.